[δείδω μή]

…τί μοι καὶ κῆτος ἐπισσεύῃ μέγα δαίμων

ἐξ ἁλός, οἷά τε πολλὰ τρέφει κλυτὸς Ἀμφιτρίτη:

[I’m afraid] that some god’s going to send a great sea-monster against me; glorious Amphitrite breeds them in numbers.

Odyssey 5.418-21

Culturally as well as geographically, the sea was central to the Classical world. These days we’re encouraged to think of the Mediterranean as something that united rather than divided the region, teeming with shipping and movement. All of this is true, but sea-faring was also deeply perilous,[1] especially in the autumn and winter. Shipwrecks and deaths at sea were common. It’s no surprise, then, that ancient Mediterranean waters were believed to be home to all manner of monstrous and deadly creatures.

Culturally as well as geographically, the sea was central to the Classical world. These days we’re encouraged to think of the Mediterranean as something that united rather than divided the region, teeming with shipping and movement. All of this is true, but sea-faring was also deeply perilous,[1] especially in the autumn and winter. Shipwrecks and deaths at sea were common. It’s no surprise, then, that ancient Mediterranean waters were believed to be home to all manner of monstrous and deadly creatures.

Prehistory and Near Eastern Precedents

We know almost nothing about very early Greek beliefs about sea-monsters, but there are a couple of possible hints that they were part of their mythology during the Bronze Age. This Minoan sealing from Knossos seems to show a man on a boat fighting some sort of sea-monster (possibly dog- or lion-headed; possibly a hippopotamus).

While at Enkomi in Eastern Cyprus, this intriguing Mycenaean-style krater shows chariots either dragging or being chased by (flying?) whales.

We’d certainly expect Bronze Age Greek sea-monster myths given how well-developed they are by the time of Homer, and their prevalence in the Near East. The first clear sea-monster stories we have about the Mediterranean come from Ugarit, one of the most important port-cities of the Bronze Age. In the cycle of stories about his exploits, Ugarit’s ambitious patron god Baʿal Hadad battles first the sea-god Yam and then Ltn, a seven-headed sea-serpent or –dragon who appears to be either an alternative form of Yam[2] or at least in his service. The myth resurfaces[3] in the Bible, of course, where it’s now God who claims to have defeated Leviathan. Some scholars also link it with Zeus’ conquest of Typhon. And it has even earlier antecedents elsewhere in the Near East: as early as the third millennium BC, the Sumerian god Ninurta defeated a seven-headed serpent.

We know little about Phoenician religion, but there’s some evidence to suggests similar primordial serpents were important in their mythology. Macrobius suggests that the serpent-eating its own tail symbolised the universe for them, while Philo of Byblos claimed that the pre-Socratic philosopher Pherecydes of Syros took his story of a primaeval battle between Kronos and Ophioneus from a Phoenician source. The Phoenician and wider Levantine god Dagan is now often seen as a fish-deity (a view popularised considerably by notorious ichthyophobe H. P. Lovecraft in stories like ‘Dagon’ or ‘The Shadow Over Innsmouth’ but drawn from a much longer tradition), but the evidence that he was in antiquity seems to be relatively scant.

Release the Κῆτος!

In Classical Greek, the usual word for ‘sea-monster’ was κῆτος (kētos). It’s entered English in ‘cetacean’, meaning whales and dolphins, but its ancient meaning was much broader, encompassing anything bigger and more ferocious than a dolphin, as the Odyssey implies when describing Scylla:

ἔξω δ᾽ ἐξίσχει κεφαλὰς δεινοῖο βερέθρου,

αὐτοῦ δ᾽ ἰχθυάᾳ, σκόπελον περιμαιμώωσα,

δελφῖνάς τε κύνας τε, καὶ εἴ ποθι μεῖζον ἕλῃσι

κῆτος, ἃ μυρία βόσκει ἀγάστονος Ἀμφιτρίτη.

She holds her head out beyond the awful chasm and fishes there, eagerly searching around the rock for dolphins and dog-fish and any bigger sea-monster she might be able to catch, which bellowing Amphitrite rears in countless thousands.

Odyssey 12.94-7

Certainly this included whales, but it also took in many stranger beasts. One of the best-known κῆτη of mythology was the one Poseidon unleashed to ravage the Aethiopian lands of King Cepheus and his queen Cassiopeia. In an attempt to end the rampage, Cepheus tried to sacrifice his daughter, Andromeda, to the monster. She was, of course, rescued by the hero Perseus, who slew the marauding κῆτος.

According to Pliny (9.11), the bones of this monster were brought back to Rome by the collector Marcus Scaurus and put on display:

M. Scaurus, in his aedileship, exhibited at Rome, among other wonderful things, the bones of the monster to which Andromeda was said to have been exposed, and which he had brought from Jaffa, a city of Judaea. These bones exceeded forty feet in length, and the ribs were higher than those of the Indian elephant, while the back-bone was a foot and a half in thickness.

Natural History 9.11

Translation by Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff

The site long associated (by Pausanias, Strabo and Josephus) with Andromeda’s rescue is the Phoenician port of Jaffa, one of a small number of sea-monster hot-spots in the Mediterranean. This was also the site where the biblical prophet Jonah embarked on his fateful sea-voyage, and in some versions of the legend is where St. George, the mediaeval Perseus, slew his own dragon.

Perseus wasn’t the only Greek hero to take on a κῆτος. Heracles – a monster-slayer from the cradle – obviously had to have a pop as well. There was the Hydra, of course, but he got to try his hand at a proper sea-κῆτος at Troy. This time it was Laomedon who’d narked Poseidon and his daughter Hesione who’d drawn the short straw and was going to be sacrificed to placate him. Here he is on a Late Corinthian krater, taking out a rather fun skull-headed κῆτος.[4]

Another hero (or possibly Heracles again) takes on another κῆτος on this late 6th-century Caeretan hydria.

There’s not particular consistency in what forms κῆτη were imagined to take. As we’ve seen, they encompass everything from big fish to serpents to skull-headed weird things. Most commonly, however, they seem to be more or less serpentine.

Waking the Dragon

There’s a blurred line between serpents, dragons and even some fish (just look at the oarfish). Greek sources generally use δράκων to refer to any monstrously large snake, whether natural or supernatural. Maritime serpents are usually an exception to this, with – as we’ve seen – κῆτος being the preferred term. But they still have considerable overlap with ‘dragons’ in their characteristics and legends. They’re gigantic, serpentine, often fiery and are slain by wandering heroes to win fair maidens. We’ve already seen how κῆτος-stories parallel and inform mediaeval dragon-lore such as the legend of St. George.

In Homer, Scylla seems to be more dragon than sea-serpent. Although she’s serpentine and feeds on the κῆτη of the sea, there’s no indication she’s actually be a sea-creature herself. This seems to have changed by the Classical period, with her increasingly becoming conceptualised as a marine creature herself. Fifth-century and later depictions show her as a sort of snaky mermaid, with a woman’s upper body and a serpent’s lower quarters, ending in a fish-tail. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses (14.8-74) she starts life as a Nereid, pursued by the fish-tailed Glaucus, before Circe transforms her into a monster.

Another border-line case is the Lernaean Hydra, slain in Heracles’ second labour. A multi-headed, poison-blooded supernatural aquatic serpent, it would tick all the boxes, save for the fact that it lived in a lake, rather than the sea. Myth also offers us the serpents that killed Laocoön and his sons.

But there were also reported encounters outside myth. Aristotle includes sea-serpents in his Historia Animalium, saying:

There are also sea-serpents, in shape greatly resembling their relatives on land, except that the head in their case is somewhat like the head of the conger. There are several kinds of sea-serpent, which differ in colour; these animals are not found in very deep water.

Historia Animalium 2.14

North Africa seems to be a particular danger-area for sea-serpents:

In Libya, the serpents, as it has been already remarked, are very large. Some people say that as they sailed along the coast, they saw the bones of many oxen, and that it was evident to them that they had been devoured by the serpents. And as the ships passed on, the serpents attacked the triremes, and some of them threw themselves upon one of the triremes and capsized it.

Historia Animalium 8.27.6

It is a well-known fact, that during the Punic war, at the river Bagradas, a serpent one hundred and twenty feet long was captured by the Roman army under Regulus, after they besieged it like a fortress, using ballistae and other engines of war. Its skin and jaws were preserved in a temple at Rome until the time of the Numantine war.

Pliny, Natural History 8.14

Alexander’s Sea-Monsters

If anyone was a magnet for weirdness and tall tales it was Alexander the Great. The tradition surrounding him – both ancient and later – includes so many sea-monster encounters that he even outdoes Heracles as a one-man monster hot-spot.

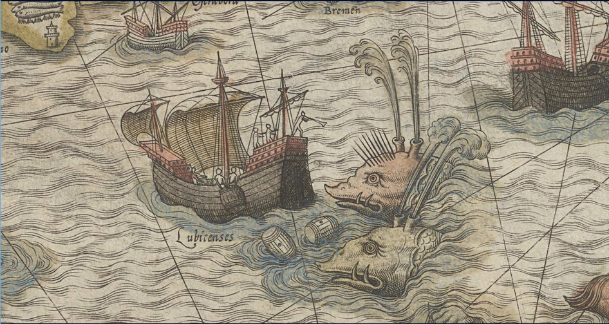

Let’s start with the relatively plausible: Arrian (Indica 30.1-9) claims that in the Persian Gulf Alexander’s fleet encountered a group of whales that blocked their passage with their spouting. We might quibble whether whales really count as sea-monsters, but, as has become increasingly clear the more we learn about the denizens of the deep oceans, the simple fact of being real is hardly enough to exclude something from being a bloody terrifying sea-monster. Whales were likely every bit as exotic, weird and frightening for the Greeks and Romans as the likes of vampire squids or goblin sharks are to us. In the 6th century AD, Procopius tells us, Constantinople was menaced by a giant whale called Porphyrios for 50 years. As recently as the late Middle Ages, there seem to be two parallel streams of whale-lore – the one dealing with whales as real flesh-and-blood animals, and the one seeing them as sea-monsters (and see, of course, Moby Dick). It’s striking how late images of whales that bear little resemblance to the real creatures persist. Alexander’s whales are striking in this connection because they provide an early example of a mainstay of mediaeval whale-as-monster lore: the use of trumpets and other loud noises to scare the beasts off.

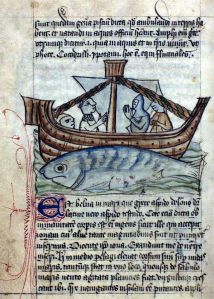

Another sea-monster well-known from mediaeval stories is the aspidochelone, the gigantic turtle or fish which is mistaken for an island. Pseudo-Callisthenes’ Greek version of the Alexander Romance includes an apocryphal letter from Alexander to Aristotle in which he describes how a hundred men landed on an island, believing there was treasure to be found there. The island promptly turned out to be a sea-monster, which dived beneath the waves, drowning them all, including Alexander’s friend Pheidon. Via the Alexander Romance, this myth made it into the Arab tradition and reappears in the Arabian Nights in the second voyage of Sinbad.

Some of the Alexander Romance’s weirder sea-monsters are to be found around Alexandria. I’m not sure whether the four gigantic glass crabs that many Late Antique and Byzantine writers claimed the Pharos stood on count, but the story of Alexander’s diving-bell definitely does. According to a version of the story by the Arabic writer Mas’udi, the harbour of the newly-founded Alexandria was infested with sea-monsters. Alexander had a glass diving-bell built and descended into the sea to look at them for himself. He then had craftsmen construct replicas of the monsters along the sea wall to scare them away.

Wot, no Kraken?

Sorry. I couldn’t find a good clip of the proper Harryhausen version. There are no krakens in Classical mythology, of course, despite what certain films might have you believe. The kraken is a northern European myth and the monster in the Perseus myth – which Clash of the Titans was based on – was really, as we’ve seen, a κῆτος.

But many believe the mythical kraken to refer to the giant squid, and that does appear in Classical sources. Aristotle and Pliny both describe the ‘polypous’. Citing the naturalist Trebius Niger, Pliny claims that:

…there is not an animal in existence that is more dangerous for its powers of destroying a human being when in the water. Embracing his body, it counteracts his struggles, and draws him under with its feelers and its numerous suckers, when, as often is the case, it happens to make an attack upon a shipwrecked mariner or a child.

Natural History 9.48

I’m going to close with the tale Pliny goes on to recount, which may be familiar to regular Res Gerendae readers. In keeping with the amphibious tendencies of many Classical sea-monsters, there was one monstrous polypous[5] that took to hunting on land:

At Carteia, in the preserves there, a polypous was in the habit of coming from the sea to the open pickling-tubs and devouring the fish laid in salt there […] At last, by its repeated thefts and immoderate depredations, it angered the keepers of the works. Fences were set up, but the polypous managed to get over with the help of a tree, and it was only caught at last with the assistance of trained dogs, which surrounded it at night, as it was returning to its prey. Awakened by the noise, the keepers were struck with alarm at the novelty of what they saw. First of all, the size of the polypous was enormous beyond all conception; and then it was covered all over with dried brine, and exhaled a most dreadful stench. Who could have expected to find a polypous there, or could have recognized it as such under these circumstances? They really thought that they were joining battle with some monster, for at one instant, it would drive off the dogs by its horrible fumes and lash at them with the extremities of its tentacles; while at another, it would strike them with its stronger arms, giving blows with so many clubs, as it were; and it was only with the greatest difficulty that it could be dispatched with the aid of a considerable number of fishing-tridents. The head of this animal was shown to Lucullus; it was as large as a cask of fifteen amphorae and had a beard, to use the expressions of Trebius himself, which could hardly be encircled. Its two arms, covered in nodules like those on a club, were thirty feet in length; the suckers or calicules, as large as an urn, resembled basins in shape, while the teeth again were of a corresponding largeness. Its remains, which were carefully preserved as a curiosity, weighed seven hundred pounds.

Natural History 9.48

Translations adapted from John Bostock

Further Reading:

Jospeh Nigg, 2013. Sea-monsters: A Voyage around the World’s Most Beguiling Map. University of Chicago Press.

Daniel Ogden, 2013. Dragons, Serpents, & Slayers in the Classical and Early Christian Worlds: a sourcebook. OUP.

John K. Papadopoulos and Deborah Ruscillo, 2002. ‘A Ketos in Early Athens: An Archaeology of Whales and Sea-monsters in the Greek World’. American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 106, No. 2 (Apr., 2002), pp. 187-227.

Richard Stoneman, 2010. Alexander the Great: A Life in Legend. Yale University Press.

[1] I’m resisting the urge for a ‘perilous periplous’ pun. And by ‘resisting’, I mean ‘sticking it in a footnote’.

[2] I’ve probably been playing too many computer games, but it’s tempting to think of it as Yam’s final form…

[3] So to speak.

[4] Even more fun if you’re one of those people who’d like to connect myths of giant monsters with possible ancient fossil-discoveries.

[5] Here I’m going to have to respectfully disagree with Anna and her Weird and Wonderful Octopus – to me it seems that Pliny has to be describing a squid. It’s the reference to the two stronger arms that clinches it. That and that squid get about that big; octopuses, as far as we know, don’t. Also, notice how I resisted a ‘perilous polypous periplous’ line. Oh.

Awesome post with awesome pictures! I particularly love that Cypriot krater with the whales 🙂

LikeLike

This Minoan sealing with a dog-like sea-monster: Could it be a very very early representation of Scylla? Because Scylla is “little dog”. Just a question a student can think about. Possibly an answer will not be feasible, there is not enough context information.

LikeLike

It’s possible, but I think it’s widely belived that ‘Scylla’ probably isn’t actually etymologically linked to the word for dog (skylax), even though as early as Homer the Greeks themselves thought it was. So the whole ‘dog’ aspect seems like a later imposition based on folk-etymology. And given that the Minoans didn’t speak Greek anyway, it’s anyone’s guess whether they shared any of the same myths.

LikeLike

Pingback: Previously On… | Ancient Worlds

Pingback: Introduction: Philip Boyes – CREWS Project

Pingback: Kraken Mythology I - the Ancient Ones - Release Your Kraken!