Board games. Board games are good, aren’t they? I discovered this rather belatedly after being a dedicated video gamer for most of my teens and early adult life. In the last few years, as I’ve been liberated from the cramped confines of student accommodation or a field archaeologist’s bedsit and acquired a circle of like-minded friends, I’ve found myself becoming more and more interested in board games. This will hardly be news to most people, but it turns out there’s a vibrant and fascinating wealth of games beyond the old childhood staples of Cluedo and Labyrinth, covering every possible subject-matter under the sun. In our semi-regular board-game meet-ups, my friends and I have played quite a few, mostly historical in theme: Escape From Atlantis; Game of Thrones; Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective. Cyclades sits waiting for us to get round to it. But there’s one game we play more than any other – Eldritch Horror.

Month: October 2016

Cambridge Festival of Ideas: the Ancient Worlds Highlights

The Cambridge Festival of Ideas runs from 17th to the 30th October. It’s one of the University’s biggest outreach events and has a wide range of talks, workshops and events open to everybody. A lot of them are specifically design to be family- or child friendly. If you’re in or around Cambridge, I highly recommend checking it out.

The Cambridge Festival of Ideas runs from 17th to the 30th October. It’s one of the University’s biggest outreach events and has a wide range of talks, workshops and events open to everybody. A lot of them are specifically design to be family- or child friendly. If you’re in or around Cambridge, I highly recommend checking it out.

The full events list is available on the website, but here are a few things that might be of particular interest to this blog’s readers:

Ruins from a Long Time Ago and Far, Far Away

The Star Wars films are well-known for popularising the idea of a ‘used future’, where the spaceships, bases and other science-fictional paraphernalia don’t gleam with the factory-new sheen of glossy and optimistic futurity but are worn-down, grimy and broken. A New Hope wasn’t the first time this had been done – witness, for example, the wonderfully industrial modelwork of Gerry Anderson’s 1960s ‘Supermarionation’ series, Thunderbirds in particular – but after Star Wars, this visual style became the norm for science fiction, to the extent that today when an SF film does opt for gleaming perfection – such as in the 2009 Star Trek reboot – it comes across as unusual and consciously retro.

The grit and grime of the used future is seen as adding to verisimilitude – it makes the sets, models and computer imagery more familiar to our own experiences of the world. In a sense it removes a dimension of estrangement from the setting, but in return it gives every scratch, battle-scar or busted piece of instrumentation a back-story. It no longer seems to exist only for the story being told, but appears to have had an existence before-hand. In short, it gives us time-depth.

So far, so obvious.

But there’s another aspect to the idea of time-depth in the Star Wars films. It’s not just equipment, vehicles and buildings which are shown to be used, but the worlds themselves. They have long histories, evidenced by the presence of ruins – a used future (or long-long-ago past-future) in the longue-durée, if you like. In particular, the first film in each of the three trilogies – original, prequel and newly-minted sequel – prominently features what we might see as ‘archaeological’ or ‘historic’ sites. Continue reading

Making Ugaritic tablets 1

I’m about to start a research project into the context of the emergence and use of the Ugaritic writing system in the Late Bronze Age city of Ugarit, on the coast of what’s now Syria. This will be a very interdisciplinary undertaking, blending linguistics, epigraphy, ancient history and archaeology, and is something I’m very excited about. The Ugaritic language and script, though, is not one I currently know (though I do have some experience with Phoenician, which is a related language, but uses a different writing system). What this means is that I have the happy task of learning Ugaritic and its alphabetic cuneiform script (and a bit of Akkadian, just for a bonus).

It quickly became apparent as I practised writing out the cuneiform that it’s slow and cumbersome to have to keep drawing the little triangles on paper and that it would be much more efficient – and authentic – to use a stylus and clay. For my first attempt I used plasticine and a makeshift stylus made out of Lego.

Introduction: Philip Boyes

I wrote an introductory post for the CREWS Project blog, where I’ll be starting work soon.

Hello! I’m Philip Boyes and I’m absolutely delighted to be joining the CREWS Project as a Research Associate from November 2016. I’m going to be looking at the Ugaritic writing system, its emergence and its context of use. Ugaritic is a fascinating Late Bronze Age adaptation of the existing cuneiform writing systems used across the Near East. Instead of each sign representing a syllable, as had traditionally been the case, Ugaritic is an alphabetic system (though one where only consonants are represented and not vowels) and was used to represent the local language of the city of Ugarit.

An abecedarium from Ugarit.

At the heart of my approach is the idea that we should explore changes in writing systems like this as we would any other example of social change – and that means getting to grips with the social context in as much detail we can, looking at how…

View original post 351 more words

Science Fiction and Archaeology: Part 2 – Grave-robbers, explorers and dilettantes

See Part 1 for why I think archaeology and science fiction share certain approaches and why they ought to go well together. This post will explore how they’ve tried and often failed.

Two Prometheuses (Prometheis?) bookend the relationship so far, and between them exemplify many of the recurring tropes which have characterised archaeological SF: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, seen by many as the first true SF novel; and Ridley Scott’s 2012 cinematic Prometheus. They take us from Gothic grave-robbers, through von Dänikenesque Chariots of the Gods to Big Dumb Objects and the Ozymandian relics of long-dead alien civilisations.

Frankenstein, illustrated by Bernie Wrightson

Now obviously, archaeology’s far from central to Frankenstein. As a discipline it was still in its infancy in 1815; anatomy and the fledgling science of galvanism were Shelley’s immediate inspirations, not the work of those adventuring plunderers who kept western aristocrats and museums in Greek vases and Aegyptiaca. Nevertheless, many of Frankenstein’s themes resonate strongly with those of archaeology. As the work’s very subtitle makes clear, it’s a work which understands the present with reference to antiquity. The link it draws between ancient myth and modern science is one that SF would revisit again and again over the next two centuries: the seeds of Chariots of the Gods? were sown there in Shelley’s masterwork. What’s more, Gothic literature’s obsession with the dead revived, the buried uncovered and the forgotten past restored blends naturally into the concerns of archaeologists. After all, what do archaeologists try to do every day if not raise the dead, give them some manner of life again with their arts? Continue reading

Previously On…

I thought it might be helpful (for me, if no-one else) to have a ‘contents page’ linking to things I’ve written elsewhere around the Web before the creation of Ancient Worlds.

Res Gerendae

Thirteen Swords: Adventures in Bronze Age Metal-working

Classical Gothic

Mummies as Monsters: Reviewing The Book of the Dead

Amphitrite’s Brood: Sea-Monsters in the Classical World

The Past in Pieces: Lego and Lost Civilisations

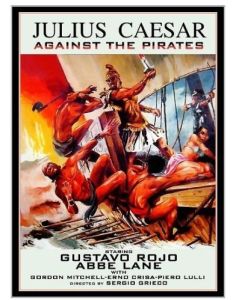

Pirates of the Mediterranean

Historical Baking – Gingerbread Viking Hall

Atlantis – Review

Visiting the Dead: Archaeology, Museums and Human Remains

Via Memoriae Classicae IV – Time Team

Via Memoriae Classicae III – Tomb Raider

Far Beyond the Pillars of Melqart

Archaeology Baking I – Minoan Glyptic

Via Memoriae Classicae IIb – Classics and Doctor Who (The 1970s Onwards)

Via Memoriae Classicae IIa: Classics and Doctor Who (The Sixties)

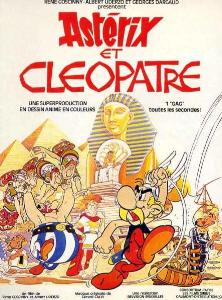

Via Memoriae Classicae I: Asterix and Cleopatra

Brickset

A Childhood in Bricks

Unlocking Research – University of Cambridge Office of Scholarly Communication

Promoting Open Access in a department – what works

Milestone – 10,000th article processed by OA Service

Science Fiction and Archaeology: Part 1 – Building worlds in the past and future

Science fiction and archaeology are two sides of the same coin. No, really. For all that one’s a literary genre and the other an academic discipline, they share a great deal in terms of goals, preoccupations and techniques. There also seems to be a good deal of overlap in the interests of practitioners: archaeologists – especially those who work actively in the field – often tend to be young, highly-educated and, in a word, geeky. With that kind of demographic, it’s no surprise that many have at least a passing interest in SF. For its part, SF has had a long-standing – if not necessarily productive – interest in the themes and motifs of archaeology. Continue reading

Science fiction and archaeology are two sides of the same coin. No, really. For all that one’s a literary genre and the other an academic discipline, they share a great deal in terms of goals, preoccupations and techniques. There also seems to be a good deal of overlap in the interests of practitioners: archaeologists – especially those who work actively in the field – often tend to be young, highly-educated and, in a word, geeky. With that kind of demographic, it’s no surprise that many have at least a passing interest in SF. For its part, SF has had a long-standing – if not necessarily productive – interest in the themes and motifs of archaeology. Continue reading

What is Ancient Worlds?

The basic answer is ‘it’s my blog’, and you can have a look here to see a bit more about who I am and what kind of things I do. To a certain extent it is going to be your typical academic’s personal blog – anything I want to talk about that I think might be of interest to a wider, non-specialist audience. But I also want to do something a little more specific with this – not an exclusive remit, but a special interest, if you like. Continue reading